This article does not apply to central lines, nor does it go into the theory of ultrasound technology. For in-depth knowledge of ultrasound technology refer to ultrasound textbooks.

Do not be afraid of an ultrasound machine. Yes, it has many knobs, buttons, and probes. It looks intimidating, but once you learn the controls, it's fairly straightforward. Every ultrasound machine has a few different probes. The only probe you need to become familiar with is the linear probe. The linear probe is the "flat" or "straight" probe. Most ultrasound machines have an attached card that describes the probes, buttons, and knobs on that specific machine. Read the card. Several manufacturers make ultrasound machines, it would be impossible to describe each one in this article.

Gather Supplies

Gather your supplies: bedside table, towel, washcloth, ultrasound gel, ultrasound machine, IV start supplies, and a chair. While you are getting set up, explain to the patient what you are doing. Explanations go a long way in helping calm the fears of patients.

Step 1. Power Up

Learn where the power switch is. Press it. Let the machine boot up. Also, always keep the ultrasound machine plugged into a power outlet. Not everyone plugs the machine back in after use and this causes the battery to discharge. You do not want to be mid-insertion and have the machine power off.

Step 2. Clean the Probe and the Patient

While the machine is powering up, clean the linear probe with whatever cleaner your facility has available for the probes. Always clean the probe, but do not clean the ultrasound screen with the same cleaner. Ultrasound screens have special cleaners. Clean the patient's skin as you would for any IV insertion.

Step 3. Configure the Machine

Select the "B" mode on the ultrasound machine. The "B" mode is the brightness mode. When the ultrasound machine is in brightness mode, what you are really seeing on the screen is a two-dimensional gray-scale image of a patient's forearm when you have the probe touching the patient's forearm. You can "brighten" the image by adjusting the "gain" knob. No perfect brightness level exists. It is ultrasound-user dependent.

Step 3A. Select the Highest Frequency

If the linear probe has frequency adjustments, select the highest frequency possible. This allows for the sharpest image possible. Not all ultrasound machines have a linear probe that is frequency adjustable. Either way, even the best images are not that sharp, but you want the sharpest images possible and that means the highest frequency possible on the linear probe.

Step 4. Position the Patient

Position the patient. If your facility has bedside tables for the patient's rooms, use them. Clean the table's top and place the towel over the table. The towel serves three purposes: it keeps the patient's arm off the cold surface, it absorbs any blood that drips onto the surface, and it serves as a quick way to dispose of all your trash when you are done.

If you do not have a bedside table, have the patient adjust themselves in bed so they can place their arm on the bed. If this is the case, place the towel folded long-ways under their arm. When you are finished, any blood that is lost does not remain in bed with the patient.

Step 5. Position the Ultrasound Machine

Place the ultrasound machine directly in front of you so that you can easily view the screen and the patient without contorting your body. You need to be comfortable when placing the IV catheter. If your body is contorted to see the screen and the patient, you are setting yourself up for failure. Do not put the machine on the other side of the bed. Ultrasound screens are just not that large, and you will miss subtle clues that appear on the screen.

Step 6. Sit Down

Starting an ultrasound-guided IV requires coordination and some finesse. You cannot control the probe and the catheter while you are standing with any measure of accuracy. Sit down and allow your body to relax. Imagine trying to lift weights and thread a sewing needle simultaneously. It's almost impossible to do. Your accuracy with the ultrasound machine will exponentially increase when you sit. The one exception is in a code blue situation. In a code blue situation, have someone hold the arm and do your best.

Step 7. Orient the Probe Correctly

On the screen and on the probe will be some style of marker so that when they are lined up the probe is oriented correctly in relation to the screen (both markers on your left or right side). Usually in a corner of the screen will be a triangle, dash, or circle and the probe will have the same style of marker. You want to make sure the marker on the probe is on the same side as the marker on the screen (I.e., if the screen marker is on the left side of the screen, the mark on the probe should be on your left as you hold the probe). When you line the screen and probe up in this manner, you have the probe in the correct orientation. Sometimes the markers can be difficult to determine. A simpler way to make sure the probe is oriented correctly is to slide the probe across the patient's forearm to your left, if the screen images move off to the right of the screen, you have the probe oriented correctly.

Step 8. Be a Painter

Apply a tourniquet. Place just a dab of ultrasound gel on the patient's forearm. The ultrasound probe needs the tiniest amount of gel to transmit ultrasound waves through. The more gel you add, the more you must remove, and the more slippery the probe becomes. You will find your optimal amount the more you use the ultrasound machine. A perfect amount does not exist. You want to move up and down the patient's forearm with the probe. Imagine being a painter and painting the patient's arm with gel. The probe must have gel under it to see into the patient's forearm. While you are "painting" with gel, you are looking for veins on the screen and how the paths of those veins change as you move up the patient's forearm. Knowing how a patient's veins change before you advance the needle and catheter will help you have a successful cannulation.

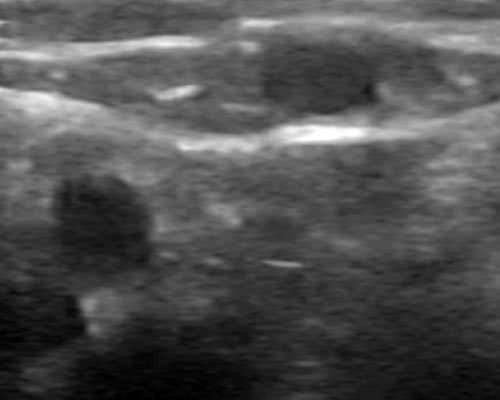

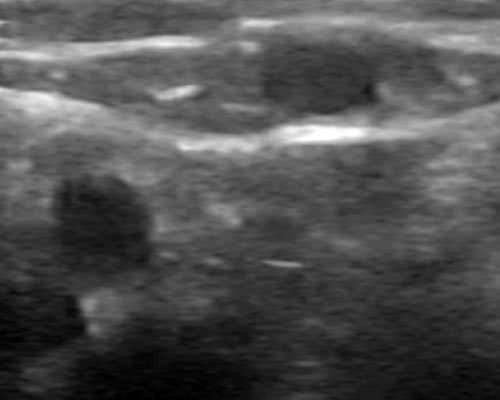

Step 9. Find a Vein

What does a vein or artery look like on the screen? They both look like black circles. (see Figure 1). As you can see in Figure 1, the image even with a 14MHz linear probe is not great. Most older ultrasounds machines only have a 10MHz linear probe. Don't get caught up in technology. A 10 MHz probe will work just fine for peripheral IV cannulations.

How do you distinguish an artery from a vein? Press the probe into the patient's forearm and hold it against the patient. A vein collapses and will remain collapsed, and an artery will pulsate. It's as simple as that, but with one caveat. Patients with extremely weak pulses can fool you. Watch the screen closely for a few seconds to determine if the black circle is pulsating.

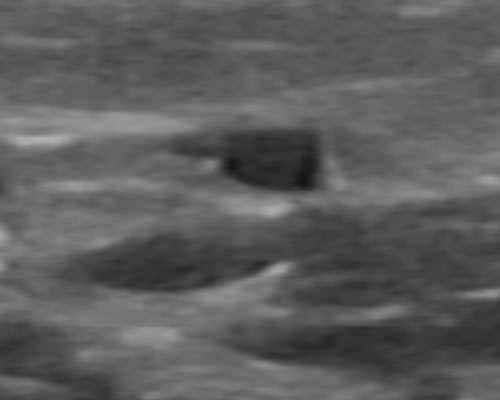

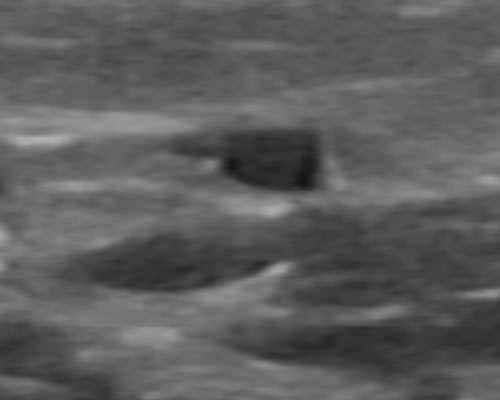

Learning how to apply the probe to a limb requires some practice to get both the positioning and the downforce correct at the same time. You cannot just press the probe into a patient's forearm while looking for veins or while inserting the IV. If you press too strongly, you will obscure the veins. You will know you have the probe correctly against a patient's skin when you see a complete image on the screen (I.e., no large solid black areas) and the veins and arteries are circles. If the veins and arteries are not circles, you have too much pressure on the probe. (see Figure 2). Optimal holding of the probe takes time to learn. Practice often. It pays off in the long run.

Step 10. Insert the Catheter

On the screen will be numbers that increase as they go down the screen. Those numbers represent the depth in centimeters into the patient's forearm. The top of the screen represents the skin of the patient's forearm. When you have located the vein you want to cannulate, look over at the depth gauge to find out how deep the vein is in the patient's forearm. Use the center of the vein as a reference point. As an example, let's say the vein's center is one centimeter down from the top of the patient's forearm. Your insertion point for the catheter will be one centimeter back from the probe.

But how do you know where to insert the needle? This is where skill and practice come into play.

In the middle of the screen will be some type of marker. It may be a simple triangle pointed down or a line of dots in the center of the screen. You carefully position the probe so that the image of the vein you want to cannulate is centered on the screen marker. On the side of the probe will be a marker that corresponds to the center of the probe. The mark on the probe matches the center marker on the screen, When the center marker on the screen is exactly over the center of the vein image, the mark on the probe is exactly over the center of the vein. Come back from the probe as far as the vein is deep in the patient's forearm, angle the catheter at a 45 ° angle to the patient's forearm, and insert the catheter in line with the mark on the probe. Make sure you are in line with the probe's marker and the patient's forearm and not angled to one side. It truly is a finesse operation. In time, it will become second nature. Believe it or not.

Never take your eyes off the screen once you are lined up and ready to insert. Taking your eyes off the screen to look down at the insertion site is the biggest mistake new ultrasound users make. No information is gained by taking your eyes off the screen, but much information is lost. When you are using an ultrasound machine to insert an IV, all the information that you need to insert an IV is on the screen. Once you look down at the insertion site and then back up on the screen, you have missed. It is almost impossible to reacquire the needle on the screen when you have taken your eyes away from the screen as a new user. Train yourself to not take your eyes from the screen.

As the needle tip pierces the vein, you will see the vein tent down then a white dot or white angular image will appear inside the vein (see Figure 3). At this point, you have pierced the vein; but again, do not look away from the screen, you still must advance the needle and catheter into the vein. Slightly move the probe forward until the image inside the vein almost disappears. It changes color from bright white to dull gray as the probe moves away from the needle tip, then hold the probe stationary and slightly advance the needle and catheter forward, making whatever adjustments it takes with the needle to keep the needle image in the center of the vein. Repeat this procedure of moving the probe slightly then the needle slightly until you feel confident you can advance the catheter the rest of the way in. You can absolutely insert the needle completely into the vein using this procedure. Once you feel confident you can insert the catheter all the way in, do so.

To verify you have a solid insertion, occlude the vein above the catheter, remove the needle and just ever so slightly release pressure and you will see blood back up into the catheter hub. Then re-occlude the vein, attach the pigtail or hub, and use the washcloth to clean all the excess gel from the patient's skin while you hold the catheter. Next, use alcohol swabs or chlorapreps around the cannulation site to ensure you reduce the bacterial load as much as possible. At this point, dress the IV site as you would any new IV. Don't forget to take the tourniquet off.

Things to Think About

New ultrasound users should practice inserting the needle and catheter all the way in before removing the needle. Nothing is worse than removing the needle too soon and then not being able to advance the catheter. Practice, Practice, Practice. Your technique will improve.

Practice using the ultrasound on patients that do not require an ultrasound-guided IV. Being able to see a patient's vein when you are learning the ultrasound technique is invaluable. Attempting to learn the ultrasound-guided technique on a patient that truly needs the technique is a recipe for disaster. You need to practice on patients with easily located veins first, to develop your targeting skills.

You can cannulate much smaller veins than you think you can. Become proficient in the ultrasound-guided technique and your days of not being able to acquire IV access almost go away, but you must practice and practice often. If you enjoy the feeling of helping patients; wait until you can gain access on almost any patient with one attempt.

People who claim to be "hard sticks" usually have veins that do not follow a straight path. Using the needle to insert the catheter completely makes hard sticks easy sticks.

Rarely will you need to use anything but an 18G catheter when using the ultrasound technique. This at first may seem bizarre or even insane, but if you examine a 22G or 20G catheter, they are just not that much smaller than an 18G. With the ultrasound machine, you can see how big the vein is and you will feel more confident using the 18G catheter. Using an 18G catheter ensures the patient can get any radiologic studies they need as well as blood transfusions or fluid resuscitations.

Longer catheters are your friend. The longer the catheter, the less chance the catheter will dislodge.

Patients with large arms with loose skin need to be reminded to keep their arms still. Catheters are secured to the skin, but nothing keeps the catheter in the vein while the skin is moving. Even long catheters will dislodge.

The more you practice with an ultrasound machine the better you will become. Hard sticks become fun challenges when you master the transverse ultrasound technique. YouTube has great videos on ultrasound IV insertions. Do not give up on yourself if you miss the first few times. Your brain is learning a new skill. It takes time to master, but it is so worth it in the end. Good Luck.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Hanniel Ortiz, CNA

3 Posts

I am open to constructive criticism Damon. I am so glad you were willing to read my entire reply. Let me know where you disagree.